Chapter 5

Chapter 5

Civil Service Discipline

5.1

It is the duty of all civil servants to work with dedication and diligence, and spare no effort in delivering quality service to the community. To maintain the integrity and efficiency of the public service, and sustain the community’s trust in the Government, civil servants have to uphold the highest standard of conduct and discipline at all times. To this end, the Government has put in place a well-established disciplinary system ensuring any civil servant who violates Government rules and regulations is disciplined and those breaking the law are brought to justice.

5.2

The Commission collaborates with the Government to maintain the highest standard of conduct in the Civil Service. With the exception of exclusions specified in the PSCO15, the Administration is required under s.18 of the PS(A)O16 to consult the Commission before inflicting any punishment under s.9, s.10 or s.11 of the PS(A)O upon a Category A officer. This covers virtually all officers except those on probation or agreement and some who are remunerated on the Model Scale 1 Pay Scale. At the end of June 2023, the number of Category A officers falling within the Commission’s purview for disciplinary matters was about 123 000.

15

Please refer to paragraph 1.4 of Chapter 1.

16

Please refer to paragraph 1.5 of Chapter 1.

5.3

The Commission’s advice on disciplinary cases is based on facts and objective evidence, supported by full investigations conducted by the relevant B/Ds. While the nature and gravity of the misconduct or offence are our primary consideration, we are also mindful of the need to maintain broad service-wide consistency in disciplinary standards, protect the right of the representations by the accused and at the same time respond to changing times and public expectations.

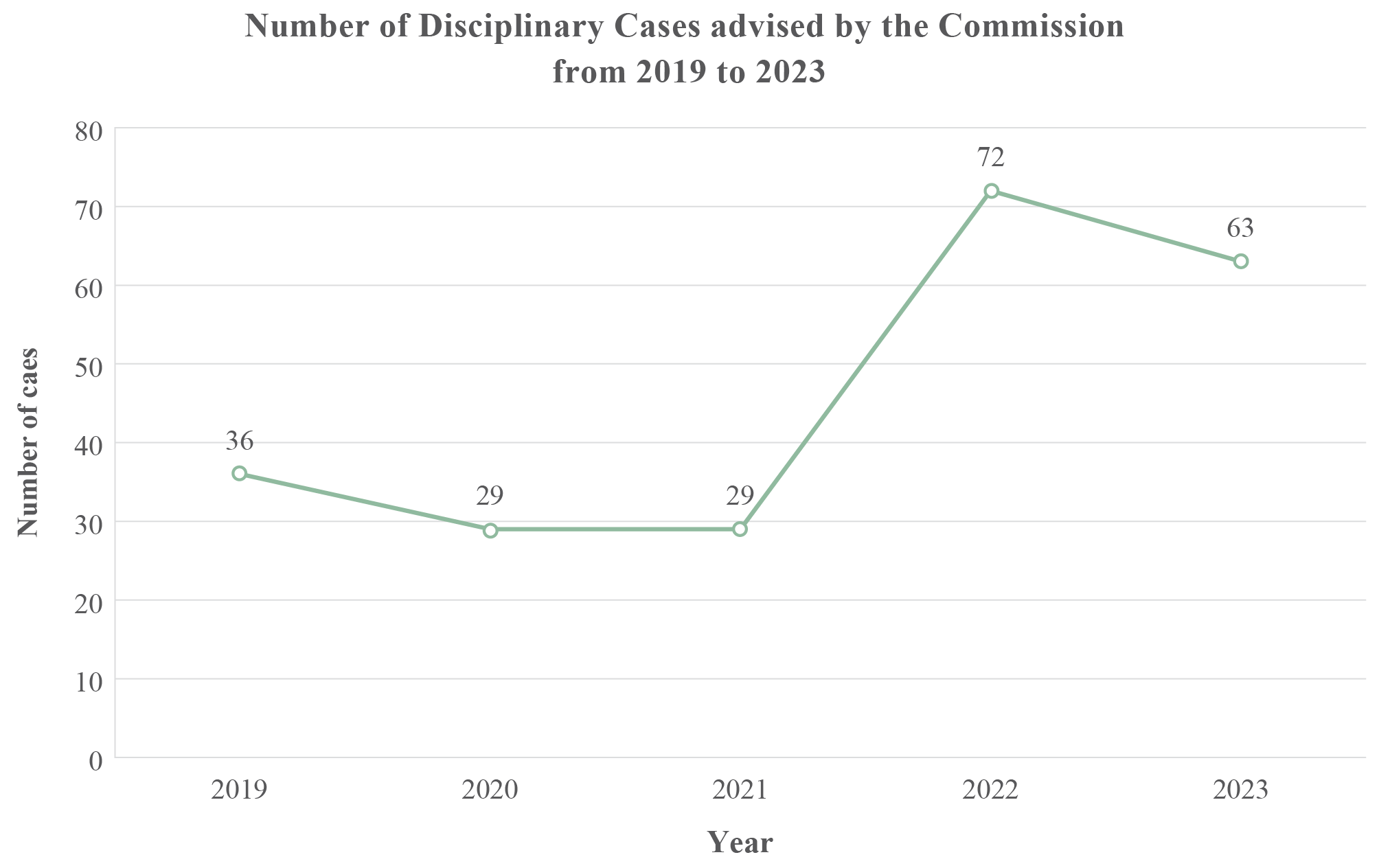

5.4

In 2023, the Commission advised on 63 disciplinary cases which had gone through the formal disciplinary procedures prescribed under the PS(A)O. As shown in the following line graph, the figure has come down slightly as compared with 2022, representing about 0.05% of the 123 000 Category A officers within the Commission’s purview. The percentage has remained low indicating that the great majority of our civil servants have continued to measure up to the very high standard of conduct and discipline required of them. CSB has assured the Commission that it will sustain its efforts in promoting good standards of conduct and integrity through training, seminars as well as the promulgation and updating of rules and guidelines.

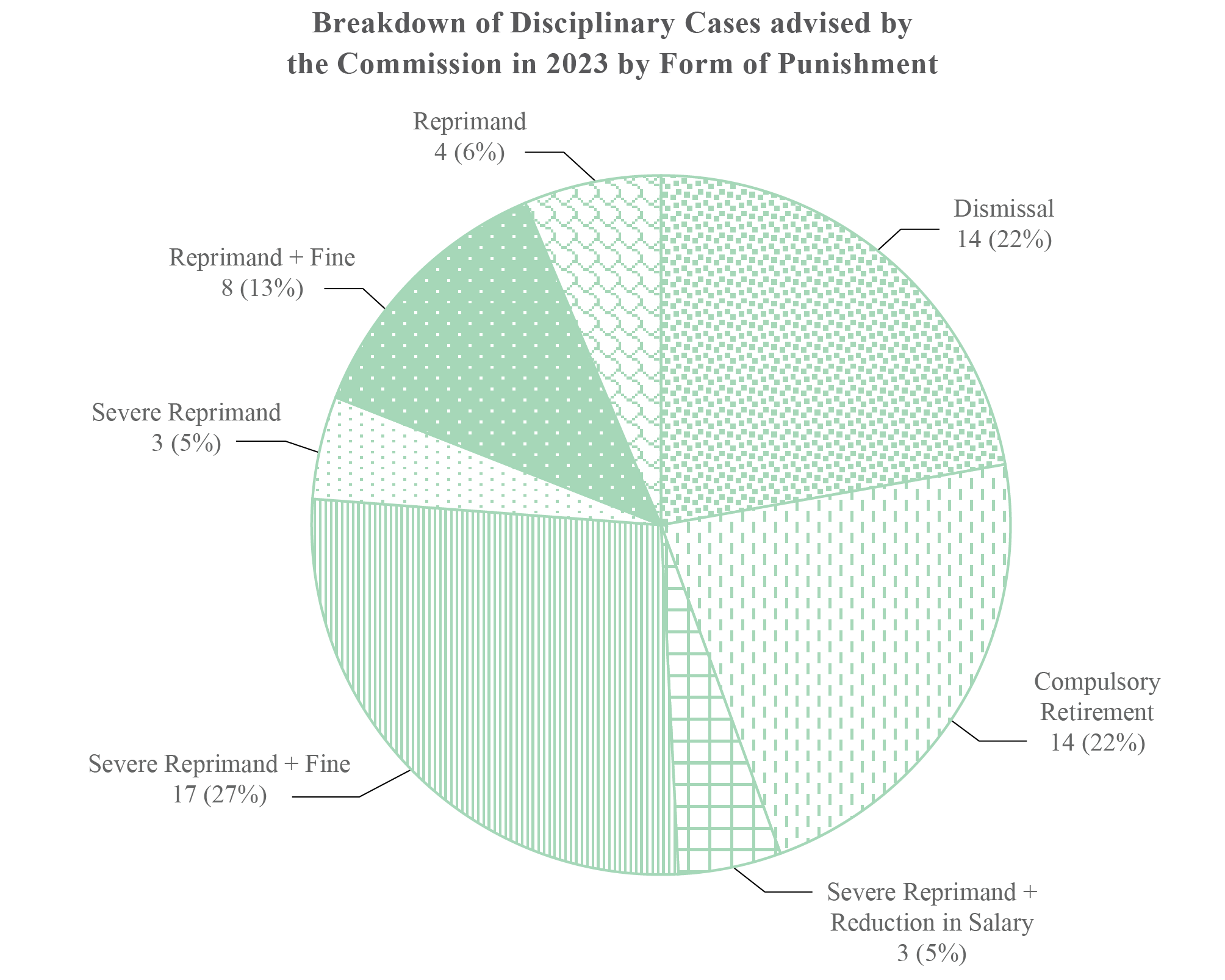

5.5

A breakdown of the 63 cases advised by the Commission in 2023 by category of criminal offence/misconduct and salary group is at Appendix IX. As depicted in the pie chart below, nearly half of the cases had resulted in the removal of the civil servants concerned from the service by “compulsory retirement”17 or “dismissal”18, while more than one third had resulted in the officers receiving the punishment of “severe reprimand”19. In about 45% of the cases, a financial penalty was added in the form of a “fine”20 or a “reduction in salary”21. These figures bear testimony to the resolute stance that the Government has taken against civil servants who have committed acts of misconduct or criminal offences.

17

An officer who is compulsorily retired may be granted retirement benefits in full or in part, and in the case of a pensionable officer, a deferred pension when he reaches his statutory retirement age.

18

Dismissal is the most severe form of punishment as the officer forfeits his claims to retirement benefits (except the accrued benefits attributed to the Government’s and the officer’s mandatory contribution under the Mandatory Provident Fund Scheme or the Civil Service Provident Fund Scheme).

19

A severe reprimand will normally debar an officer from promotion or appointment for three to five years. This punishment is usually recommended for more serious misconduct/criminal offence or for repeated minor misconduct/criminal offences.

20

A fine is the most common form of financial penalty in use. On the basis of the salary-based approach, which has become operative since 1 September 2009, the level of fine is capped at an amount equivalent to one month’s substantive salary of the defaulting officer.

21

Reduction in salary is a form of financial penalty by reducing an officer’s salary by one or two pay points. When an officer is punished by reduction in salary, salary-linked allowance or benefits originally enjoyed by the officer would be adjusted or suspended in the case where after the reduction in salary the officer is no longer on the required pay point for entitlement to such allowance or benefits. The defaulting officer can “earn back” the lost pay point(s) through satisfactory performance and conduct, which is to be assessed through the usual performance appraisal mechanism. In comparison with a “fine”, reduction in salary offers a more substantive and punitive effect. It also contains a greater “corrective” capability in that it puts pressure on the officer to consistently perform and conduct himself up to the standard required of him in order to “earn back” his lost pay point(s).

Reviews and Observations on Disciplinary Issues

5.6

The Commission has been working in close partnership with the Government to identify, develop and promote good practices in the management of the Civil Service. As the expectations and demands of the community towards the Government and civil servants have continuously grown, the Government sees the need to update the Civil Service Code, as proposed in the Chief Executive’s 2022 Policy Address, to clearly spell out the constitutional roles and responsibilities of civil servants, as well as the core values and standards of conduct that they should uphold nowadays. The Commission fully supports this initiative. Having consulted the Commission’s views on the updated Code in December 2023, CSB has proceeded to conduct staff consultation and brief the Legislative Council Panel on Public Service. We look forward to the promulgation of the updated Code in 2024.

5.7

The Commission has also been working closely with CSB to pursue the initiative in the Chief Executive’s 2022 Policy Address to enhance the Civil Service disciplinary mechanism. We have requested CSB to keep the disciplinary punishment standard under regular review to align with the expectations of the community. As early and swift action is just as important to achieve the desired punitive and deterrent effects, we consider it necessary for CSB to take the lead to review and identify measures to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of handling disciplinary cases. We are pleased to note CSB has responded positively to our views.

5.8

Separately, we are glad to see the Secretariat on Civil Service Discipline (SCSD) has maintained its out-reach visits to B/Ds to explore scope to enhance mutual efficiency in processing disciplinary cases. Recognising that personnel assigned and the investigation techniques they possess are pivotal to the successful conclusion of disciplinary cases, SCSD has responded positively to the Commission’s suggestion and launched in the year capacity building workshops for investigation work on disciplinary cases. Such workshops are not just targeted to appointment practitioners but also extended to departmental managers who are responsible for day-to-day staff management. The Commission will continue to collaborate with CSB and provide feedback and suggestions to facilitate its pursuit of the training initiatives.

5.9

Apart from deliberating and advising on the appropriate level of punishment for the cases it received for advice, the Commission also makes observations on them and initiates discussions with CSB to explore scope for improvement in handling disciplinary cases or staff management. In the ensuing paragraphs, we will highlight some of the observations and recommendations we have tendered in the year.

5.10

In accordance with the established mechanism, pending criminal and disciplinary investigation/proceedings, the B/D concerned is empowered to invoke s.13 of the PS(A)O22 to interdict an officer from duties and exercising the powers and functions of his public office. While interdiction is only an administrative measure carrying no presumption of guilt, the management should take into account all relevant factors in totality to evaluate the risk involved in allowing an officer to continue to work. An interdicted officer should not be re-instated if disciplinary action is likely to be taken with a view to removing him from the service.

22

Having regard to all relevant factors, an officer may be interdicted from duty –

(a)

under PS(A)O s.13(1)(a) if disciplinary proceedings under s.10 of the PS(A)O have been, or are to be, taken against him, which may lead to his removal from service;

(b)

under PS(A)O s.13(1)(b) if criminal proceedings have been, or are likely to be, instituted against him which may lead to his removal from service under s.11 of the PS(A)O if convicted; or

(c)

under PS(A)O s.13(1)(c) if inquiry of his conduct is being undertaken and it is contrary to the public interest for him to continue to exercise the powers and functions of his office.

5.11

In deciding whether an officer should be interdicted from or re-instated to duty, B/Ds should –

(a)

duly consider the key parameters such as the nature and gravity of the alleged criminal offence/misconduct laid against the officer and the possible conflict with his official duties, the likely harm/risk posed to the general public, as well as the public reaction and perception to the officer remaining in office; and

(b)

be decisive and critical in the process, particularly when job-related misdeeds are revealed.

Case 5A illustrates the importance for a Department to be decisive and swift in action to interdict a defaulting officer.

Case 5A

In handling his counter duties, a staff member had the chance to deal with members of the public and get access to their personal data. As he was facing insolvency and unable to borrow money, he abused the personal data of his clients to help himself take out loans. His misdeeds were unearthed when a victim complained to his Department, and the case was reported to the Police. During the on-going criminal investigation on his alleged offence, the officer was allowed to continue to assume his counter duties for over two years, and was only interdicted from duty after being charged with “Misconduct in public office”. The officer was eventually punished by dismissal for his conviction of the offence.

Without doubt, the staff member’s then alleged offence was serious, as it had invited a public complaint, and involved direct conflict with his counter duties as well as abuses of his official position. Allowing a bankrupt officer to have access to personal data continuously through their frequent contact with the public during the criminal investigation was apparently inappropriate, as it would run the risk of recurrence of the same offence. In fact, as revealed in the case, his insolvency and unsuccessful attempts to borrow money from colleagues were already known by his supervisors before his committing the offence. Had the Department disallowed him to handle sensitive information at that point in time according to the rules for tackling staff insolvency, he might not have the chance to commit the current offence.

5.12

Even though the gravity of some alleged criminal offences/misconduct may not be so severe that warrants a removal disciplinary punishment, B/Ds should still critically review the suitability for the officers concerned to stay in their original posts/offices continuously when he is re-instated to duty, having regard to various factors such as their rank and job nature. Case 5B shows that a Department should carefully consider posting for a defaulting officer to avoid adverse impact on the operation of an office.

Case 5B

An officer was convicted of a non-duty related offence in the district where he was working and entrusted with law enforcement duties. He was re-instated to his original post when the Disciplinary Authority came up with the recommendation of imposing a non-removal punishment on him.

As a middle-ranking officer occupying a supervisory position, the officer had to work closely with other law enforcement agencies to carry out his law enforcement duties in the same district again after he was re-instated to his original post.

Due to his criminal offence, we could not rule out that there might be negative perception cast on the officer’s continuous discharge of official duties in the same post and the same district. On the Commission’s advice, the Department subsequently transferred the officer to another district office.

5.13

As noted, some criminal offences/misconduct acts could be nipped in the bud if the supervising officers were vigilant enough to detect anomalies in workplace and take appropriate staff management/deployment measures at an early stage to mitigate any possible risks. Admittedly, some inconvenience/difficulties in office operation may be brought about by staff re-deployment or interdiction, particularly when the related criminal/disciplinary proceedings are lengthy. However, public interest must always prevail. B/Ds have to give sufficient weight on those key parameters and exercise due sensitivity whilst deciding on staff interdiction or re-instatement. The departmental or grade management should intervene proactively to give steer and support as necessary. CSB should be consulted if in doubt.

Staff awareness

5.14

Pursuant to section 13(1) of the Public Service (Disciplinary) Regulation, civil servants are required to report to their B/Ds if criminal proceedings are being instituted against them, except for certain non-duty-related traffic offences for which the reporting requirement is exempted23. The Commission has noted with concern that time and again civil servants were found to have failed to comply with the reporting requirement, with the usual claim that they are not aware of such requirement or that they have interpreted it as not applicable to their own case, as shown in a number of disciplinary cases received by the Commission last year. Such reporting failure delays the B/Ds’ considerations and actions as required. In a serious case, the defaulter, who had not been disciplined for his earlier unreported conviction in a timely manner, had committed the same offence a year later and was removed from the service subsequently.

23

CSB Circular No. 2/2009 on “Reporting of Non-Duty Related Traffic Offences under the Public Service (Disciplinary) Regulation” sets out that the reporting requirement is applicable to all cases in which an officer has been charged with a criminal offence or summonsed to appear as a defendant before a court of criminal jurisdiction, except criminal proceedings and convictions of the minor non-duty related traffic offences.

5.15

The Commission is thus pleased with CSB’s positive response in reviewing the matter. With the promulgation of CSB Circular No. 4/2023 on 28 July 2023, the reporting requirement has been tightened up, whereby civil servants have to report their arrest by a law enforcement agency irrespective of whether criminal proceedings are eventually instituted against them. In this way, B/Ds concerned could consider the need for staff interdiction or other administrative arrangement as appropriate at an earlier stage. To take on board the Commission’s suggestions, CSB also issued in November 2023 guidelines and reminders to B/Ds on the conduct of briefing/refresher sessions for all new recruits and serving staff to heighten their awareness and understanding of the reporting requirements, failing which would be subject to disciplinary punishment to be meted out on a stringent standard. The Commission welcomes the introduction of the above measures and guidelines, and hopes that they would be helpful in bringing down the incidence rate of non-compliance.

5.16

Apart from the reporting of criminal proceedings, the Acceptance of Advantages (Chief Executive's Permission) Notice has been another common area of breaches that is often attributed by staff to their unawareness of the rules in spite of the mandatory re-circulation of the relevant guidelines to all staff at regular intervals. In a case advised by the Commission last year, the supervisor and several colleagues of the offending officer had made loans to him that exceeded the prescribed limit repeatedly over a long period. Whether or not the case had indeed reflected a collective lack of knowledge of the relevant statutory requirements, the Commission has invited the Department to review the need to improve the circulation arrangement of the rules and offer assistance/counselling to its staff, especially those at junior ranks, to understand their responsibility of full compliance.

5.17

For departments that are responsible for delivery of public services, they have usually formulated more detailed rules and systems in order to ensure the fairness and openness of the provision of such services to the public as well as to prevent public complaints or fraudulent activities. While foul play by staff is rare, the Commission noted with concern that abuses had been found repeatedly in a Department in the past year. All the defaulting officers were punished for misconduct of abusing their official positions to help other people acquire public services without adhering to the rules stipulated by the Department. While it is basic to equip the handling staff with good work knowledge, it is as important to instil in them a proper sense of fair play in allocating limited public resources and the alertness to uphold a high level of probity required of a civil servant. In this connection, the Commission has requested the Department to review its existing control mechanism and enhance its staff training with a view to avoiding further recurrence of abuse.

Staff management and improvement measures

5.18

It is beyond doubt that defaulting officers are held personally accountable for their misconduct acts. At the same time, B/Ds should be on constant alert to ensure the robustness of the control/monitoring mechanism of their departmental operation/systems. If job-related offence/misconduct happens, supervising officers and the management have the duty to identify any breeding grounds or circumstantial factors and to take remedial action immediately to avoid recurrence of similar misconduct. In tendering its advice on a case in which the defaulting officer had entered his office outside working hours to embezzle the public’s lost properties found and kept by the Department, the Commission has asked the Department concerned to review the related procedures holistically with a view to plugging any loophole therein in light of the responsibilities it placed on frontline staff and the involvement of public properties.

5.19

Cases 5C and 5D show that effective daily staff management is key to the maintenance of a high standard of staff conduct and discipline.

Case 5C

In a Department, an officer had called in sick consecutively for various types of minor illnesses without diagnostic details. Even when he exhausted his vacation leave and failed to provide valid medical certificates to cover all days of absence, his supervisors had maintained a compassionate approach and refrained from initiating formal proceedings to tackle his unauthorised absence given his previous medical history of leg disease. Instead, the supervisors only reminded him repeatedly of the need to support his sick leave applications with valid medical certificates, as well as the dire consequences of unauthorised absence. However, the officer ignored the reminders and even refused to respond to his supervisors at the later stage.

Even though the case was escalated to the headquarters, the departmental management had not intervened to steer the taking of more robust actions. With the delay in action, the situation of unauthorised absence had dragged on for another two months before the Department proceeded to take formal disciplinary action against the officer and punished him by dismissal.

The Commission considers that the officer’s suspected abuse of sick leave could have been deterred had the Department instituted appropriate management action at the outset as provided by the stipulated guidelines.

Case 5D

In another case, a junior rank officer was found having dumped a file of his office in the rubbish bin of another department located on another floor of the same office building. While he confessed his unauthorised destruction of an official file, he did not see the seriousness of his misconduct. Not only did he insist his good intent to assist his office in disposing old files, he even blamed his supervisors for not agreeing to his act. He further revealed that he had previously shredded some other files. Taking into account all relevant factors of the case, the Government subsequently punished the officer by a reprimand and a fine.

On closer scrutiny of the case, it was noted that the officer had already received 11 verbal/written advice over the years for various types of failings, omissions, insubordination or misconduct in discharging his duties, many of which were related to his disregard of office procedures and/or defiance against supervisors’ instructions. However, the supervisors/divisional management had never taken disciplinary actions, not even summary ones, but only resorted to administrative actions all along despite seeing such not taken seriously by the officer.

The Commission had raised its serious concern to the Department about its excessively tolerant attitude and lax approach adopted towards the repeated misdeeds of the defaulting officer. The Department’s attitude in handling the misconduct of the officer was also called into question. Had heavier punishments and stern disapproval been meted out earlier, the officer should have been impressed on the standard of discipline expected of him and might not have committed the current misconduct act repeatedly.

5.20

The wilful disregard of discipline and blatant breaches of rules in these cases reflect poorly not only on the defaulters but the management capability of their supervisors and the management as well. B/Ds should conduct regular reviews and surprise checks to ensure effective running of their staff management mechanisms. Frontline supervisors should be reminded to adopt a responsible attitude to handle misconduct cases and be equipped with the know-how to deal with repeated misconduct acts. Senior management directions should be given for decisive actions, where necessary.

Effective daily staff management is key to the maintenance of a high standard of staff conduct and discipline.